Wavenumber

In the physical sciences, the wavenumber is a property of a wave, its spatial frequency, that is proportional to the reciprocal of the wavelength. It is also the magnitude of the wave vector. Its usual symbols are  ,

,  , σ or k, the first three used for one definition, the last for another. The wavenumber has dimensions of reciprocal length, so its SI unit is m-1 and cgs unit cm−1 (in this context formerly called the kayser, after Heinrich Kayser).

, σ or k, the first three used for one definition, the last for another. The wavenumber has dimensions of reciprocal length, so its SI unit is m-1 and cgs unit cm−1 (in this context formerly called the kayser, after Heinrich Kayser).

Contents |

Definition

It can be defined as either

, the number of wavelengths per unit distance, where λ is the wavelength, sometimes termed the spectroscopic wavenumber, or

, the number of wavelengths per unit distance, where λ is the wavelength, sometimes termed the spectroscopic wavenumber, or ,the number of wavelengths per 2π units of distance, sometimes termed the angular or circular wavenumber, but more often simply wavenumber.

,the number of wavelengths per 2π units of distance, sometimes termed the angular or circular wavenumber, but more often simply wavenumber.

For electromagnetic radiation in vacuum, wavenumber is proportional to frequency and to photon energy. Because of this, wavenumbers are used as a unit of energy in spectroscopy. In the SI units, wavenumber is expressed in units of reciprocal meters (m−1), but in spectroscopy it is usual to give wavenumbers in reciprocal centimeters (cm−1). The angular wavenumber is expressed in radians per meter (rad·m−1).

In wave equations

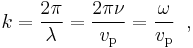

In general, the angular wavenumber k, the magnitude of the wave vector, is given by

where ν is the frequency of the wave, λ is the wavelength, ω = 2πν is the angular frequency of the wave, and vp is the phase velocity of the wave.

For the special case of an electromagnetic wave in vacuum, where vp = c, k is given by

where E is the energy of the wave, ħ is the reduced Planck constant, and c is the velocity of light in vacuum.

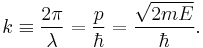

For the special case of a matter wave, for example an electron wave, in the non-relativistic approximation:

Here p is the momentum of the particle, m is the mass of the particle, E is the kinetic energy of the particle, and ħ is the reduced Planck's constant.

In spectroscopy

In spectroscopy, the wavenumber  of electromagnetic radiation is defined as

of electromagnetic radiation is defined as

where λ is the wavelength of the radiation.

The historical reason for using this quantity is that it proved to be convenient in the analysis of atomic spectra. Wavenumbers were first used in the calculations of Johannes Rydberg in the 1880s. The Rydberg–Ritz combination principle of 1908 was also formulated in terms of wavenumbers. A few years later spectral lines could be understood in quantum theory as differences between energy levels, energy being proportional to wavenumber, or frequency. However, spectroscopic data kept being tabulated in terms of wavenumber rather than frequency or energy, since spectroscopic instruments are typically calibrated in terms of wavelength, independent of the value for the speed of light or Planck's constant.

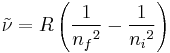

For example, the wavenumbers of the emissions lines of hydrogen atoms are given by

where R is the Rydberg constant and ni and nf are the principal quantum numbers of the initial and final levels, respectively (ni is greater than nf for emission).

A wavenumber can be converted into energy E via Planck's relation:

.

.

It can also be converted into frequency via

where  is the frequency, and cn is the speed of light in the medium.

is the frequency, and cn is the speed of light in the medium.

In colloquial usage, the unit cm−1 is sometimes referred to as a "wavenumber",[1] which confuses the name of a quantity with that of a unit. Furthermore, spectroscopists often express a quantity proportional to the wavenumber, such as frequency or energy, in cm−1 and leave the appropriate conversion factor as implied. Consequently, a phrase such as "the energy is 300 wavenumbers" should be interpreted or restated as "the energy corresponds to a wavenumber of 300 cm−1." (Analogous statements hold true for the unit m−1.)

See also

References

- ^ See for example,

- Fiechtner, G. (2001). "Absorption and the dimensionless overlap integral for two-photon excitation". Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 68 (5): 543. Bibcode 2001JQSRT..68..543F. doi:10.1016/S0022-4073(00)00044-3.

- US 5046846, Ray, James C. & Asari, Logan R., "Method and apparatus for spectroscopic comparison of compositions", published 1991-09-10

- "Boson Peaks and Glass Formation". Science 308 (5726): 1221. 2005. doi:10.1126/science.308.5726.1221a.